Hundreds of miles away from the political quagmire that is Washington, D.C., former Congressman Ron DeSantis navigated a different kind of swamp on Wednesday. And this one’s in no need of draining. Quite the contrary.

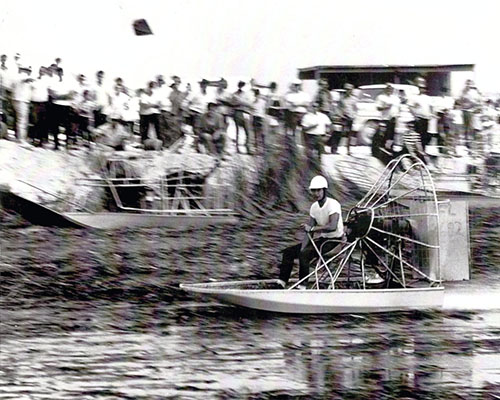

Hours after unveiling a newly minted environmental plan, which includes plans to allow runoff from Lake Okeechobee to flow south into Florida Bay, the state’s Republican nominee for governor joined a fellow named “Alligator Ron” — real name Ron Bergeron — on a half-hour airboat tour of the Everglades. And just like Washington, a pack of reporters stayed hot on his tail, pointing their cameras and microphones from separate boats.

“We had to lag you guys a little bit,” DeSantis, joined by Bergeron, said afterward. “He killed a couple of pythons on the way back … reached in and just manhandled them.”

Advertising himself as a “Teddy Roosevelt-style Republican,” DeSantis said Wednesday that restoring the Everglades and maintaining Florida’s environment in general was a priority to him. It will certainly be a priority for his general election campaign, as he moves from courting Republican hardliners in August to independent and undecided voters in September as he runs against Democrat Andrew Gillum.

And so, with Democrats hounding him as a “sham environmentalist,” DeSantis released his first-ever policy paper as a gubernatorial candidate: a four-part plan to protect the state’s water supply and beaches by banning fracking and drilling off the coast, restoring water flow and preventing toxic algae blooms fed by foul water discharges from Lake Okeechobee. And then he made a traditional campaign romp through the River of Grass.

“To me, anything is on the table,” DeSantis said. “I’m not somebody that thinks you just throw a lot of red tape and it solves problems but there are instances where you can do a targeted approach that could make a difference.”

The policy roll-out — which critics say belies a poor voting record during three terms in Congress — includes a pledge to create a task force to study a massive red tide outbreak off the state’s southwest coast, and a promise to push legislation “on day one” banning fracking. DeSantis also said he’ll continue pursuing projects already underway to bridge the Tamiami Trail over the Everglades and build a massive water reservoir south of Lake Okeechobee.

Only hours after resigning from the U.S. House of Representatives in order to focus on his campaign, the conservative Republican began visiting waterways plagued by toxic blue-green algae and promoting his plans to protect the environment. DeSantis said his administration would focus on curbing excessive discharges from Lake Okeechobee by restoring the Everglades and completing the construction of a southern reservoir, a feat he said wouldn’t be possible without nearly $1 billion in federal funding.

He also said he would look to address the consequences of rising seas on coastal communities, centralize the enforcement of water quality standards under the governor-appointed head of the Department of Environmental Protection, and honor the voter-backed Florida Forever amendment forcing the state to spend hundreds of millions of dollars every year on conservation projects. He said he’s open to the purchase of land near Lake Okeechobee.

In releasing his plan, DeSantis emphasized — as he often does — his close relationship to President Donald Trump as a key advantage he has in securing federal funds for Everglades restoration and reducing polluted discharges.

“To accomplish this, our next Governor must have the ability to work with President Trump, his administration, and Congress to finally deliver on Everglades restoration for Florida,” DeSantis’ platform states. “No one is better suited to accomplish these goals than Ron DeSantis.”

Having a plan to address the discharges of foul water from Lake Okeechobee is crucial for DeSantis. The release of billions of gallons of polluted water from the lake has fouled the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuaries three out of the last five years, including this summer. During the Aug. 28 primary, Gov. Rick Scott, running for U.S. Senate against a nominal opponent, had one of his worst performances in Martin County, which is fed by the St. Lucie River.

DeSantis says the Everglades is the “cornerstone” of that plan, and following an airboat ride five miles out from an Alligator Alley boat ramp in Broward County, Bergeron, a former head of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, said the two men would work on restoration efforts.

“I’ve spent most of my life trying to save one of the natural wonders of the world. And I’m really honored to work with our next governor,” Bergeron, clad in fatigues, told reporters.

But Democrats and environmental groups picked at DeSantis’ environmental plan Wednesday, warning that it lacked detail regarding efforts to address the cause of water pollution and failed to mention climate change — something the outgoing governor has been loathe to address.

“This plan is incomplete,” said Frank Jackalone, Florida Chapter Director for the Sierra Club.

Jackalone said DeSantis’ plan would do nothing to “address pollution at its source,” and argued that the state’s reservoir plan is, by its own admission, inadequate in terms of cleaning dirty water. Jackalone, whose organization was among several that sued the state in order to demand that Florida Forever money be spent on land acquisition and conservation efforts rather than overhead, also worried that DeSantis’ support for the amendment was worded in a way that suggest he’d support an ongoing appeal of the ruling filed by the Florida House and Senate.

In a conference call with reporters set up by the Florida Democratic Party, Aliki Moncrief, the executive director of Florida Conservation Voters, also said DeSantis’ new plan “doesn’t’ line up with his track record” in Congress, which includes cosponsoring a bill that would block federal oversight of waterways. DeSantis also voted with almost every other Republican in the House for a 2016 spending package that slashed funding and projects by the Environmental Protection Agency by $108 million

Moncrief and Jackalone both criticized DeSantis’ for dismissing efforts to address carbon emissions and other causes of climate change, which may exacerbate algae blooms and other environmental problems.

“Climate change was fueling those things,” Moncrief said. “There’s really no connection to that in the DeSantis plan.”

In Broward Wednesday, DeSantis wouldn’t explain what he’d do differently than Scott. But he said he’s not a climate denier.

“I think human activity contributes to our environment. I have always thought that. I’m also not somebody who is on the political left that says if there are more hurricanes, it is because of climate change. Sometimes I think they get a little carried away,” he said, likening climate activists to religious fanatics. “I’m not in the pews of the church of the global warming leftists. I’m a Teddy Roosevelt conservationist. It’s just a different analysis.”

In some ways, DeSantis benefits from a primary campaign in which Big Sugar — a political powerhouse now blamed for contributing to the toxic algae blooms clogging Lake Okeechobee’s tributaries — spent millions attacking him. DeSantis’ televised rebuke of Big Sugar during a Aug. 8 debate in Jacksonville was unprecedented for a major Republican candidate for governor and brought him unusual praise from environmental groups. He was endorsed by the Everglades Trust in his primary against Commissioner of Agriculture Adam Putnam, whom he mocked by calling him an “errand boy for U.S. Sugar.”

n contrast, Democratic nominee Andrew Gillum has said that climate change is a “real and urgent threat” and that as mayor of Tallahassee, he led an initiative to reduce carbon emissions in the city by 40 percent. Like DeSantis, Gillum promises to clean up Lake Okeechobee, protect the Everglades and prioritize clean water sources. Gillum has also sworn off money from Big Sugar, and picked a running mate in Chris King who framed a losing gubernatorial campaign around his opposition to Florida’s sugar industry.

The DeSantis campaign took a shot at Gillum’s record Wednesday, noting that he once supported a coal plant in North Florida (before voting against it) and accused the mayor of inflating the city’s reduction of carbon emissions. Additionally, one of Gillum’s closest friends and senior campaign advisors is longtime friend Sean Pittman, who is a registered lobbyist for Florida Crystals, a major sugar company. Democrats, meanwhile, say DeSantis is only now pretending care about the environment.

Either way, with algae blooms fouling rivers and coastline, and the Everglades under constant duress, both candidates know they need to show they have plans for the state’s environment in order to court Florida voters.

“Florida candidates know how important natural resources are to our ecology and economy,” Celeste De Palma, Everglades policy director for Audubon Florida, said in a statement. “The River of Grass provides drinking water to one in three Floridians, and no candidate can hope to win without focusing on environmental issues like the Everglades.”