- Jenny Staletovich

- Miami Herald

So much rain so early in the wet season has led to a slow-moving crisis across South Florida: what to do with all the water before things get really bad.

To avoid drowning wildlife in the central Everglades, and avoid fouling the Treasure Coast with dirty water from Lake Okeechobee later in the season, the South Florida Water Management District began back-pumping water into the lake over the weekend. Then this week, the U.S. Corps of Engineers opened flood gates into the western Everglades, flooding nesting grounds for the endangered Cape Sable seaside sparrow for the second year in a row.

The dilemma pits flood control against conservation efforts and while it’s an old battle in Florida, water managers have now faced back-to-back years of emergency operations.

“There’s nothing to call it but unfortunate,” said Julie Hill-Gabriel, deputy policy director at Audubon Florida. “There really is no cost-free option on the table right now.”

Just last month, much of the state was under a drought warning, facing threats from wildfires and water shortages. Then the wet season roared in the first week of June, dumping more rain in a week than the amount typically seen for the entire month. The central Everglades got hit the hardest, with 15 inches falling on average.

That filled up the vast conservation areas. Water Conservation Area 3A, the largest of the three straddling Miami-Dade and Broward counties, is now about two feet above where it should be, said Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commissioner Ron Bergeron.

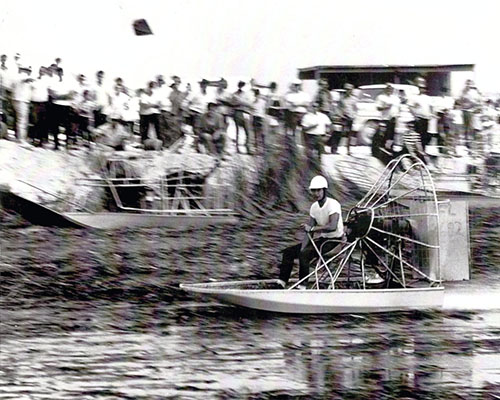

On Thursday, Bergeron escorted reporters to a tree island south of Alligator Alley, where his grandfather first built a camp in 1946, to highlight conditions. The problem was obvious as soon as Bergeron, the commission’s Everglades point man, stepped off an airboat with his daughter and onto his partially submerged dock.

“This whole environment has a lot to do with our quality of life,” he said. “Nine million people depend on it for their drinking water, so it ain’t no play game.”

The second week of June, after the heavy rain, water started flowing into the conservation area three times faster than it was leaving, Bergeron said. The commission restricted public access to protect stressed wildlife stranded on shrinking tree islands. Bergeron said he also began urging Gov. Rick Scott and South Florida water managers for relief. Over the weekend, the district took the unusual step of pumping treated water from stormwater treatment areas normally headed south back into Lake Okeechobee, along with a number of other efforts to move water off the peninsula.

At the same time, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers became concerned that a levee protecting western suburbs might be at risk. District workers are now inspecting sections of a levee along I-75 daily.

“The challenge with the three water conservation areas, specifically Water Conservation Area 3 is it’s got many of the same challenges as Lake O. There’s very limited outflow,” said Corps spokesman John Campbell.

The decision to move water into sparrow nesting grounds in the western Everglades comes at a particularly dicey time for the birds.

In April 2016, record winter rain drenched low-lying nests across the marshes. Sparrows, whose numbers have dropped 60 percent since 1992, nest in six locations in the park. But only two provide suitable conditions, an important fact since their nesting patterns show how water historically flowed through the marshes.

In 2014, sparrow numbers dropped below 2,915, a critical threshold indicating conditions were off. That required water managers to go back to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to reassess how water is moved across nesting grounds. Based on a U.S. Geological Survey study, federal wildlife officials concluded nests needed to be kept dry through July 15 in the western Everglades.

Opening the gates now will likely flood nests with eggs and chicks, said Service spokesman Ken Warren.

“There’s just no way around that,” he said. “But what we took into consideration was there was growing concerns that there could be possible risk to human health and safety because of high water.”

In addition to moving water west, water managers are also moving water south under the Tamiami Trail bridge into Shark River Slough. A second stretch of the bridge is expected to be completed in 2019 that could triple the amount of water flowing into the park under a decades-old Everglades restoration project called Modified Waters. The project is expected to vastly improve the flow of freshwater through the park and into Florida Bay, where 25-square miles of seagrass died last year as the bay withered.

“When Mod Waters is implemented, you won’t have to micromanage this system as much as we have over the last decade,” Bergeron said.

But until then, water managers could be in for a summer juggling competing crises.

“Three weeks ago we were so worried about having a dry wet season that we were talking about putting pumps on the lake to be able to pump it out. Now we have the rain,” Hill-Gabriel said. “This is going to continue to be a challenge. It’s the ultimate unfortunate depiction of the lack of options we have in a system that isn’t yet restored.”